We’re on a slope where monetary policy has become increasingly ineffective in promoting real economic growth. Every crisis was met with monetary easing that caused debt and other imbalances to accumulate over time, and that caused the next crisis to be bigger than the previous one.

William White, Former Chief Economist of The Bank of International Settlements

Cracks on the Wall in 2021

A few weeks ago, US Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen announced that the US government is heading towards default if Congress does not lift its ‘debt ceiling’. As we all know from economic history, the default of the United States would be a catastrophic ‘financial Armageddon’. With the US being the largest economy in the world, this is alarming news.

On the other side of the world, China’s second largest property company, Evergrande is facing a debt crisis. The default of Evergrande may have potential spillovers with the residential market being worth 29% of China’s GDP (Rogoff and Yang, 2020). Excess leverage of the Chinese corporate sector does not spell financial confidence. Some are claiming that this is potentially a Chinese ‘Lehman Brother’ bubble bound to pop like the 2007-08 global financial crisis (GFC).

In Europe, since the advent of Covid-19, the European Central Bank bought virtually all the government bonds (quantitative easing) of European countries like Italy and kept its interest rates at zero percent. No private investor is willing to buy government bonds at this stage. The only market players in this area are central banks.

Something strange is happening across the world economy. We are witnessing imminent cracks in the global financial system. It’s difficult to predict what may occur in the next few months or years, but one thing is clear – the global economy is extremely fragile. The net worth of many individuals and households are bound to crash sooner or later.

Introduction

Virtually everyone understands that getting into excess debt leads to trouble. Whenever someone sees a ‘red’ balance in their bank accounts, they panic and try to do everything they can to either lower their deficits or pay back the debt. Financial circumstances matter to people. Saving before spending is the common wisdom. This logic applies to governments too. Except they have the ‘printing press’ with government-controlled (or owned) central banks to fill their coffers (as lender of last resort), on top of tax revenue.

Whilst it may be true to claim that governments are different to individuals and households, its economic decisions have significant consequences on our livelihoods.

It’s been a year since the Covid-19 pandemic began. In contrast to last year’s 3% economic contraction, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that the world will face positive economic growth of 6% for 2021 (IMF, 2021). It seems that high vaccination rates are allowing cities and regions to get out of lockdowns. The United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union and other parts of the world are opening up to the rest of the world. In hindsight, financial circumstances appear better than 2020.

However, there are serious questions as to whether this will be the case in the medium term. In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, many governments across the developed world have accumulated debt levels well-beyond their annual economic output (Gross Domestic Product – the value of every single thing sold on every single shelf around NZ and the value of every single person who worked for a whole year) and the net worth of these governments are heavily in the negative (considering the assets and liabilities of governments).

Table 1: Net Worth of Governments

| Country | 2016 |

| United Kingdom | -141 |

| Finland | -109 |

| United States | -69 |

| Austria | -41 |

| Canada | -29 |

| Germany | -22 |

| Australia | -21 |

| Switzerland | 12 |

| South Korea | 41 |

| New Zealand | 46 |

| Norway | 384 |

This is an unprecedented level of debt during peacetime. Instead of fiscal surpluses, we have so far witnessed the exact opposite from governments. Unfortunately prudence is not a popular term for government officials. Low interest rates from central banks induced more governments to borrow more money. They decided to get the money now instead of the future. Instant gratification took precedent over delayed gratification.

In addition, central banks across developed economies printed trillions of dollars out of nothing to stimulate the world economy away from the recession. They also lowered its interest rates to zero-bound levels. In essence, central banks have made borrowing extremely cheap for everyone, including governments. But the such low interest rate levels are unprecedented.

Spending has become easier. Saving money is not rewarded. Inflation undermines the real value of the dollars in your bank account. This forced individuals to speculate in the stock market or the housing market for a decent return. Unproductive zombie firms have been propped up without falling, forcefully maintaining low unemployment levels without ‘creative destruction’ (Banerjee and Hofmann, 2018, 2020)

But what happens if these markets face downturns again later? Everyone may lose everything. Can they react in a similar manner to the GFC of 2008 or Covid-19? Are bailouts from governments even feasible? I’m not entirely sure.

This is why governments and central bank policies matter to all of us. This essay will explore the few key variables that culminated into the current state of financial affairs. The moral hazard problem; the public debt precedent set by the 2007-08 GFC; the doubling down of debt with the responses to Covid-19 and finally the potential long-term ramifications of these responses.

In times of uncertainty, policymakers pursued these policies for correct short-term reasons, but the decisions have created unintended consequences for the future. Central Banks cannot raise interest rates, nor can they suck the printed money out of the system for fears of creating a worse recession. They are now stuck at a corner by kicking the ‘recession’ can to the future. In the words of former Federal Reserve economist Bill Dudley, central banks are “running out of fire power” (Dudley, 2020).

The decisions in response to the pandemic were understandable. In the face of uncertainty, it is entirely rational to have pumped money into the economy, and to have spent billions on the wage subsidy and other fiscal programmes across the developed world – including New Zealand.

But the net consequences is that the financial system does not look healthy or sustainable. In contrast to optimistic scenarios, the reality is that the world is at a crisis point.

Overall, the decisions by governments and central banks have created a financial system that is chugging along entirely on the “excessive build-up of debt” (White, 2021). This is unsustainable and a form of a financial crisis will loom the world soon. It is uncertain how this next crisis will occur, but economic history tells us that risk is always present (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2009).

We will explore the reasons why that is the case. The origins of the problem started with the end of the stagflation period under Paul Volcker.

The Rise of Moral Hazard

The only way to contain the economic damage of a financial fire is to put it out, even though it’s almost impossible to do that without helping some of the people who caused it.

Ben Bernanke, Henry Paulson and Timothy Geithner, on their policy responses to the GFC

Moral hazard is a common economic term used to define human behaviour when people get incentivised to take more risks for greater profit at the expense of the other party. Another term for this is the ‘principal-agent problem’. For example, if I have health insurance I have the incentives to be more careless with my health, assuming the insurance company will bail me out when I need heart surgery based on my heart attack. It’s the problem of taking more risk when you are not as personably liable.

On similar grounds, beginning with the Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, central banks intervened in the economy whenever there was a downturn in the stock market. In contrast to health insurance where there is a risk premium demanded by these companies, what Greenspan did was essentially bail out investors and financiers for free repeatedly. Under Greenspan, the Federal Reserve intervened by lowering the Effective Federal Funds rate during the 1987 stock market crash, the 1994 Mexican peso crisis, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the collapse of Long Term Capital Management and the dotcom bubble in 2000 (Rudd, 2009). By easing monetary conditions whenever there was a downturn, he propped up the stock market and economic activity. Essentially, the Fed was providing free insurance to investors. During his reign between 1987 and 2006, he was world renowned for presiding over the ‘Great Moderation’ period of moderate economic growth, low unemployment, low inflation and ‘managing’ the global economy well.

But if you continue bailing out the people that fail, they are more likely to make riskier decisions, assuming a massive profit by taking that risk. Why wouldn’t they!? The Fed had their backs. The higher the S&P 500 went, the more riskier investments they made. We see this in the growth of new financial products in the likes of subprime mortgages market (Mortgages lent to people that do not have the collateral, capital or employment to buy homes, but loaned out on the basis of higher risk. These were sliced and diced into non-risky assets into the form of Collaterized Debt Obligations) and credit default swaps (financial instruments purchased on the assumption that other parties will fill for bankruptcy, which is essentially a bet) during this era. This was a timebomb in the residential sector that was bound to fall, but for the medium term, as long as house prices continue to go up, things looked rosy. Then the global financial crisis happened beginning in 2007.

The Road to High Government Debt Levels: GFC 2007-08

New Zealanders might recall the tumultuous period during the 2007-08 GFC. The fall of Lehman Brothers and other financial institutions across the stock market left investors in panic mode. The financial ‘cancer’ of subprime mortgages and CDOs spread to the entire global financial system. Banks such as Northern Rock in England faced bailouts from the British government and the Bank of England. With the help of the Federal Reserve, the United States had to spend USD$1.5 trillion in bailouts and tax cuts to stimulate the economy and stir away from the global recession. It was a transfer of a banking crisis into a public debt crisis.

Alongside the Federal Reserve in the United States, other central banks – such as the ECB, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan – begun the process of what economists call quantitative easing (the printing of money) and reducing their interest rates to low record levels. This was to save the economy from falling into further recession.

Millions of people lost their homes, life savings and their livelihoods. Many people became unemployed and lost jobs – some even permanently became redundant. It was an extremely unpleasant sight at the time. Alan Greenspan’s reputation had tarnished completely.

It affected the New Zealand economy as well. NZ unemployment jumped from 3.6% in 2007 to 6.1% by 2010. As a response, under both the Fifth Labour government and Fifth National government, we pursued fiscal stimulus programmes. Thanks to our prudent fiscal measures beginning in 1994 to 2008, we were able to respond well. Under John Key’s National government, our government debt levels went up from 5.4% debt to GDP in 2008, to 25.4% of GDP by 2014. The Reserve Bank under then- Governor Alan Bollard dropped interest rates by 5.75% to stimulate the New Zealand economy (Bollard and Ng, 2012). New Zealand did not need to pursue quantitative easing.

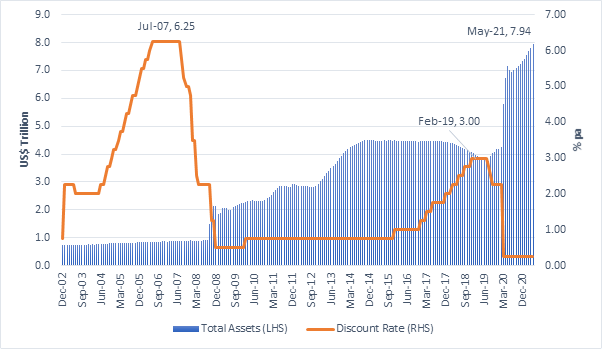

According to Ben Bernanke (the former Federal Reserve Chairman and successor to Greenspan), it was imperative for policymakers in American ‘to do everything it takes’ to stop the world economy facing a modern ‘Great Depression’. They bailed out financial institutions bound to fail, they provided liquidity to the US Treasury by purchasing government bonds and rapidly expanded their balance sheets. The total assets of the Fed increased from USD$1 trillion to USD$2 trillion by 2009, and the Federal Funds rates at 0.75 as indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

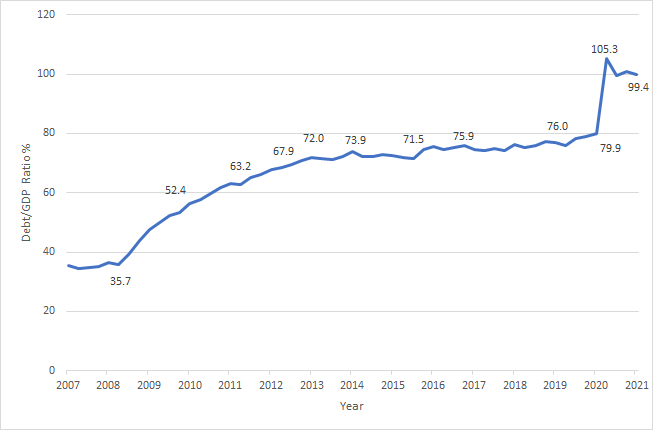

Under Obama, the US Federal government pursued fiscal stimulus programmes such as the American Recovery Reinvestment Act of 2009. This programme alone added USD$840 billion to the budget deficit. As indicated Figure 2, the federal debt held by the public ballooned from 35.7% in 2008 to 75.9% of GDP by 2017, which is more than double before the GFC.

Figure 2:

Other economies such as The European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan and other developed economies spent their way out of the problem. The banking crisis originating in American transformed into a public debt crisis across the developed world (except for fiscally prudent nations such as Australia and New Zealand), culminating into a sovereign debt crisis in Europe – also known as the 2011 Euro crisis.

The GFC revealed excess public borrowing. Countries in Europe such as Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Cyprus were unable to repay or refinance their debt obligations to their bond holders. Many looked to other European Union member states for financial assistance or even bail outs. An extreme example is Greece. The small Southern European country received series of 100 billion euro bailouts from the International Monetary Fund and the European Union (Voigt, 2012). Germany was the most generous of lenders. Yet despite this, Greece defaulted in 2015 (and is currently barely staying afloat with Greek government debt levels remaining well above 100% at 210% of GDP as of 2021). Many European economies are also floating along thanks to the financial support from prosperous economies such as France and Germany, and low interest rates from the European Central Bank.

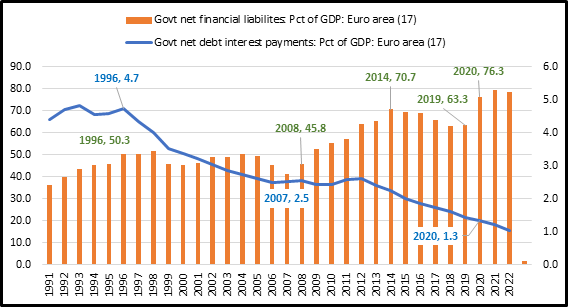

Figure 3 shows that governments have been induced to borrow more as interest payments continue to decline. The European system is not healthy by any means. Debt levels and leverage are far too high, encouraged by central bank intervention and help from other countries.

Figure 3:

In conclusion, the responses to the GFC saved the global economy facing an economic depression. However, this came at a cost. The banking crisis turned into an inevitable public debt (or sovereign debt crisis). In the United States, public debt continued to accumulate with little indication of deleveraging or fiscal restructuring. Meanwhile, Greece created political and economic turmoil in Europe, amalgamating into populist sentiment in Europe. With the Brexit vote in 2016, the European Union and the euro currency’s future remains uncertain.

If the Greek default created such geopolitical turmoil, imagine what the circumstances would be if any of the major G20 economies face financial trouble. In addition, the initial quantitative easing from central banks restarted the economy following the GFC, but it incentivised governments, households, companies to all take more debt rather than less. The world essentially buckpassed the financial crisis to the future as a short-term band aid. Then in 2020, Covid-19 hit the world starting in Wuhan, China, forcing governments and central banks to make drastic decisions.

The Fiscal and Monetary Consequence of Covid-19

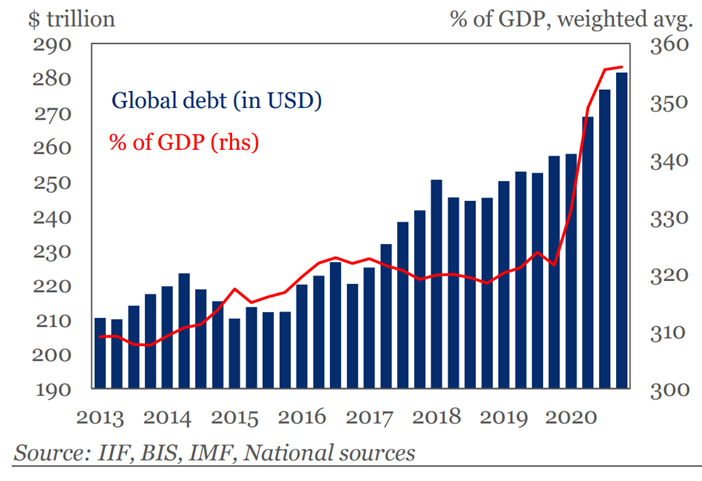

The supply shock to the global economy came from a pandemic. Governments and central banks again took swift decisions. The fiscal and monetary responses to Covid-19 were very similar to the GFC, except the scale and size of the quantitative easing from central banks and deficit spending of governments were far larger. For the Euro zone the average gross financial liability levels were close to 120% of GDP. The United was 141% and the United States was 146%. Under President Biden, the US Federal government’s fiscal deficit was 15.9% of GDP for 2021. For the Euro zone on average it was 7.2% and New Zealand was 4.2% deficit (OECD, 2021). Before in 2008, the ratio of global household, corporate and government debt to GDP was 280%. As shown in Figure 4, in response to the pandemic, in 2020, this ratio had grown by 75% to 355% (IIF, 2021). The world has now mortgaged our future by getting into more debt now.

Figure 4:

Governments around the world have never spent this much money in response to a pandemic in peacetime. The deficits created during the 2007-08 GFC look miniscule in comparison.

In monetary policy, the central banks have pumped more money and liquidity into the system than ever before, shown in Figure 5. ‘Trillions’ are being swashed around the global financial system (For context, 1 trillion is five and a half times New Zealand’s GDP). Bank rates are now virtually zero around the world – see Figure 6. The banks have little firepower left to tackle another financial crisis later down the track. Monetary policy has become less effective as a result of all of these responses beginning from the GFC.

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

When the United States and the rest of the developed world entered zero-bound rates during the GFC, former Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa noted that when Japan was adopting zero bound interest rates and quantitative easing policies beginning in the early 1990s, he never expected other countries such as the United States to follow suit (Shirakawa, 2014). Yet, other central banks did, and they all entered a road of no return.

Conclusion

The global economy has entered a cross road, unable to turn back towards a period of relative normalcy. Starting with the fiscal and monetary responses to the GFC, governments have accumulated record debt, and central banks lowered its rates and printed money to stir the economy away from prolonged recessions. We have kicked the can down the road to an even more precarious future.

Both governments and central banks are stuck into a corner. Governments’ cannot stop spending, because otherwise unemployment rates would erupt; central banks cannot lift rates for the fear of sovereign default and collapses of heavily indebted companies. The public cannot stop buying inflated assets with the ‘fear of missing out’. Rising inflation and low interest rates incentivise people to stop saving and risk their future wealth through speculation. All of these government responses create bad incentives across the whole global economy.

On monetary policy, the late macroeconomist John Maynard Keynes wrote in 1936 that “If, however, we are tempted to assert that money is the drink that stimulates the system to activity, we must remind ourselves that there may be several slips between the cup and the lip.”

The effectiveness of monetary policy has now been nullified with rates close to zero percent. What can central banks do to respond to the next crisis? Bailouts? Further quantitative easing? Economists cannot predict the future, but we can anticipate risks from recent trends.

Contemplating that future is bleak. The era of normalcy following the end of the Cold War seems like a distant past. The period of ‘normal’ interest rates and sustainable debt levels seem implausible at this stage. The trends have been towards more debt, lower rates and more money printing. What will governments and central banks around the world do? And more importantly, when will this madness end? We will soon find out in the near future.

References

Alan Bollard and Tim Ng, “Learnings from the global financial crisis,” Sir Leslie Melville Lecture, Australian National University, Canberra (9 August 2012).

Alan Rappeport, “As debt default looms, Yellen faces her biggest test yet,” The New York Times (23 September 2021).

Bill Dudley, “The Fed Is Really Running Out of Firepower”, Bloomberg (28 October 2020).

Emre Tiftik and Khadija Mahmood, “Global Debt Monitor: COVID Drives Debt Surge—Stabilization Ahead?” Institute of International Finance (17 February 2021).

International Monetary Fund. “IMF Public Sector Balance Sheet Statistics: Database.”

Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, This Time is Different (Princeton University, 2009).

Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang. “Has China’s Housing Production Peaked?” China & World Economy 29:1 (2021), 1–31.

Kevin Rudd, “The Global Financial Crisis”, The Monthly (February 2009).

Kevin Voigt, “Eurozone approves new $173B bailout for Greece,” CNN (21 February 2012).

Mark Dittli, “Central banks keep shooting themselves in the foot,” Interview with William White, The Market (6 November 2020).

Masaaki Shirakawa, “Is Inflation (Or Deflation) ‘Always and Everywhere’: A Monetary Phenomenon? My Intellectual Journey in Central Banking,” BIS Paper 77e (2014).

Matt Egan, “‘Financial Armageddon’. What’s at stake if the debt limit isn’t raised,” CNN Business (8 September 2021).

OECD.Stat.

Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann, “Corporate Zombies: Anatomy and Life Cycle,” BIS Working Papers No. 882 (2020)

Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann, “The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences,” BIS Quarterly Review (2018)

The Economist: “How should recessions be fought when interest rates are low?” (21 October 2017).

US Federal Reserve, “Federal Debt Held by the Public as Percent of Gross Domestic Product.”

US Federal Reserve, “Credit and liquidity programs and the balance sheet.”

William White, “It’s Worse than ‘Reverse’: The Full Case Against Ultra Low and Negative Interest Rates,” Working Paper No. 151 (New York: Institute for New Economic Thinking, 2021).

Yardeni, and Mali Quintana. “Central Banks: Monthly Balance Sheets” (Yardeni Research, Inc. 2021).